Pacamara is a hybrid of two quite different varietals: Pacas and Maragogype. Created in a Salvadoran lab in 1958, it took over 30 years to develop - and the result is far greater than the sum of its parts. We dig into its origins, its remarkable parents, and why a chance mutation spotted by a security guard in Nicaragua has us head over heels for the rare Yellow Pacamara.

The Pacamara: A Love Letter to Coffee's Most Fascinating Varietal

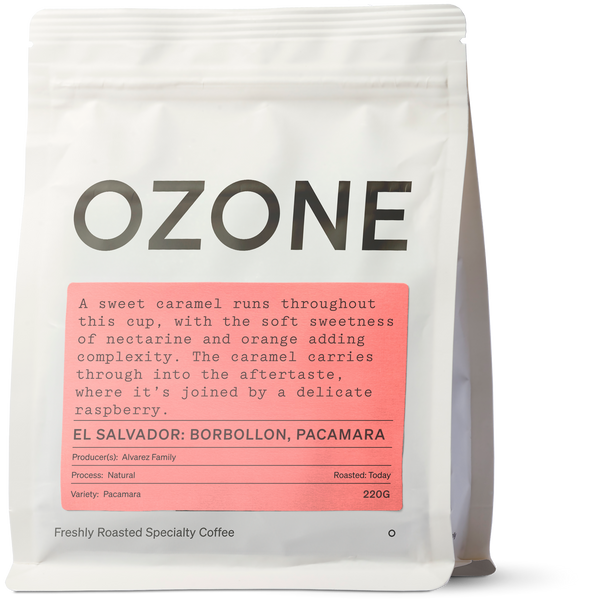

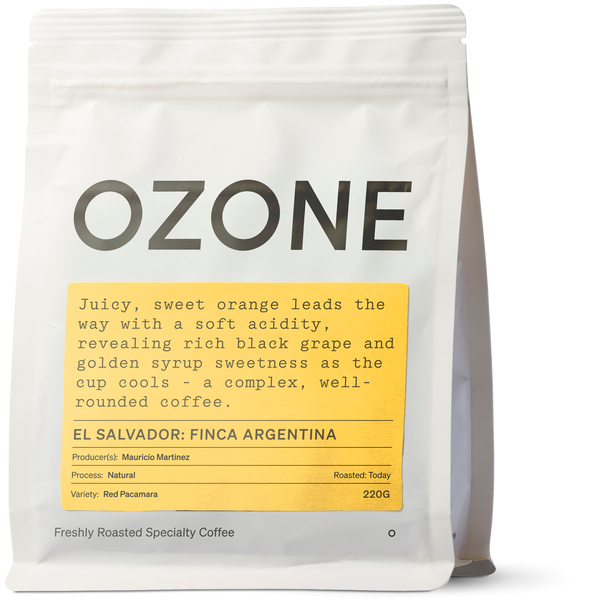

Here at Ozone, we love Pacamaras. And we love to share that love.

This varietal has confused, bemused, and ultimately captivated us for years. We've spent considerable time researching, tasting, and discussing it over more than a few rums at origin with producers. What follows is our attempt to share everything we've learned about this remarkable coffee.

A quick caveat: much of this information comes from our own findings or from sources we believe to be true - including those rum-fuelled conversations at origin with producers whose first language isn't English. Any errors are ours alone.

What is Pacamara?

Pacamara is a hybrid of two quite different varietals: Pacas and Maragogype. Understanding its parents is essential to appreciating what makes this coffee so special.

The Pacamara Family Tree

Pacamara

Created at the Salvadoran Institute for Coffee Research (ISIC), this cross between Pacas and Maragogype took over 30 years to stabilise. The result is far greater than the sum of its parts—one of specialty coffee's most complex, unpredictable, and rewarding varietals. When it's good, it's extraordinary.

The Mother: Pacas

Pacas is a natural, spontaneous mutation of Bourbon - El Salvador's answer to Villa Sarchi in Costa Rica or Caturra in Brazil. It thrives in the Salvadoran climate where it was first discovered.

The variety was discovered in 1949 at San Rafael farm on the Santa Ana Volcano - the same farm we still buy from today. The story goes that Don Francisco Pacas had noticed certain trees performing exceptionally well since around 1930. He replanted three-quarters of a manzana with seed stock from these special trees, and the results were remarkable: 20% higher yields than the rest of the farm.

When a visiting botanist, Dr. Cogwill, came to investigate, the trees had been nicknamed 'San Ramon Bourbon.' Dr. Cogwill meant to label them properly but forgot. Back at Florida University, he remembered only the name of the family who owned the farm (the Pacas family) and so 'Pacas' was born.

In the cup: Pacas is similar to Bourbon but tends to be slightly less sweet. Its higher yield seems to have a small effect on the final cup. We've found some amazing Pacas lots, but it's rare for Pacas to outperform a Bourbon on the cupping table from the same farm - though we have seen exceptions, notably at San Rafael itself.

The Father: Maragogype

Pronounced mar-rah-go-jeepeh, this mutation of Typica really earns its 'mutant' tag. It's huge - known as the giant of Arabica coffees, with tall plants, massive leaves, and oversized fruit. The variety first appeared in 1870 in the Maragogipe province of Bahia, Brazil.

The distinctive large beans have created commercial interest, sometimes to the detriment of the cup - Maragogype can fetch a premium based on appearance alone, regardless of taste. We've seen plenty from Brazil, Guatemala, and Mexico, and we've heard claims that larger beans produce more flavoursome coffee. Our experience doesn't support this. The quality has everything to do with husbandry and environment, not bean size.

In the cup: High acidity with bright citrus notes like lemon and grapefruit, plus floral properties. But honestly, finding a truly excellent Maragogype is rare - many are just plain awful, old, or poorly processed.

How Pacamara Came to Be

The romance happened not in a smoky bar but in a laboratory - the Genetic Department of the Salvadoran Institute for Coffee Research (ISIC) in 1958. Scientists were running breeding programmes with various varietals, and one experiment crossed Pacas with Maragogype. Like any good partnership, they each contributed part of their name.

The lab work involved isolating parents until scientists obtained pure plants, which gave seedlings to many lines. The goal was finding offspring that were disease-resistant, strong, high-yielding, and healthy. It took over 30 years to develop and distribute the F5 (fifth generation) that we know today as Pacamara.

There's a small complication: both Pacas and Maragogype have dominant genes, so around 10–20% of offspring fail to become true Pacamara and remain one parent or the other. These need to be spotted at the nursery stage. Pacas plants are easy to identify; Maragogype requires more attention.

Why Pacamara is Greater Than the Sum of Its Parts

This is where it gets genuinely interesting.

Our experiences of Pacas and Maragogype individually have been mixed at best. As varietals, it's rare to find amazing lots from either - Maragogype in particular tends toward flat, plain, and boring. Finding exceptional Pacas has taken considerable work.

But put these two together and you get one of the most unpredictable, interesting, and delicious varietals in specialty coffee. Of course, bad examples exist - and when Pacamara is bad, it's very bad. Vegetal, mushroomy, dirty, cardboard-like Pacamaras are far more common than they should be. We've done more work and asked more questions about these coffees than any other varietal we buy.

Our Work with Limoncillo

We first encountered Yellow Pacamara in 2012 when visiting Finca Limoncillo. We begged Erwin Mierisch to sell us some, but he explained they were using the entire crop to create seedlings for expansion. Soon, he promised, it would be available.

A word on our philosophy: we would never tell a coffee farmer what to do. All the experiments we've run with producers are experiments they've wanted to run - mostly their ideas, prompted by us asking 'what would you like to try?' Telling a farmer what to do would be like them telling us how to roast. We know very little about coffee growing, and we'd be coming at it from a far lower knowledge base than theirs.

That said, some wonderful discoveries have emerged from collaboration. The experiments with Limoncillo's natural Pacamaras were the brainchild of Eleane Mierisch, who noticed significant differences on the cupping table depending on drying methods. The team decided to turn the coffee every hour instead of every two hours, expecting a cleaner cup with retained body.

Everyone got the memo except one worker, who continued turning every two hours. When we visited the farm to cup that year's samples, the hourly-turned coffee was indeed cleaner - the word used was 'elegant.' But while elegant was fantastic, we missed the somewhat bonkers craziness of previous years' naturals.

Then Eleane remembered the 'mistake' lot. She roasted a sample. The first word spoken after tasting was 'funky!' And so the names were born: Elegant and Funky. Eleane has since developed these processes further, experimenting with different drying bed thicknesses to speed up or slow down drying.

Roasting Pacamara

Pacamara beans aren't fundamentally different to roast, but their larger size makes them susceptible to a few specific challenges.

Drying: The first 80% of roasting reduces water content from about 10-12% down to nearly zero. With larger beans, if the roast moves too quickly, the centre won't dry as thoroughly as the outer parts - leading to an under-roasted centre and over-roasted exterior.

Temperature: Pacamaras tend to roast at slightly lower temperatures than other varietals (a trait shared with Maragogype). They go through the same processes but typically reach first crack and second crack a few degrees Celsius cooler.

Exothermic reactions: First and second crack release heat. For Pacamaras, there's increased risk that this extra heat will accelerate the roast beyond your planned profile, quickly pushing beans toward over-roasted territory.

Visual assessment: Sight is generally the least useful sense when judging roast progression, and this is doubly true for Pacamaras. They often appear uneven and lighter than they actually are.

Batch size: The larger beans take up more space. As a rule of thumb, the same weight of unroasted Pacamara occupies about 10% more volume than smaller varietals - something to account for to avoid inconsistencies from an under- or over-filled drum.

The Yellow Pacamara: Something Truly Special

This relatively new varietal was the inspiration for writing this article.

Yellow Pacamara is a natural mutation from red fruit to yellow, first spotted among the red-fruiting trees at Limoncillo by a security guard. It's not unheard of for coffee plants to have a one-off colour change, so initially it was noted and forgotten. But that security guard later became farm manager (hard work pays off), and he brought it back to the Mierisch family's attention.

They isolated the tree, collected its beans separately, grew seedlings, and repeated the process until they had enough plant stock for production. With coffee taking four years to reach full harvest, you can appreciate how long this takes.

The first year of full production yielded just 240kg, sold through the Los Favoritos Fincas Mierisch auction in two lots. We tried to buy both, but when the price climbed, we had to step back. One lot went to friends in Japan; we secured the other.

In the cup: The difference from red-fruited Pacamara is striking. Cupping blind, we found abundant yellow fruits (peach and apricot) with a creamy mouthfeel and notes of pineapple and tropical fruit. Compare that to the red, which delivers lemon pith on the front end and those bright, vibrant hop-like notes you find in craft beer, with a creamy edge and remarkable sweetness throughout. Super different, equally interesting, and most importantly - both absolutely delicious.

Why We Keep Coming Back

Pacamara remains one of the most challenging, rewarding, and endlessly fascinating varietals we work with. When it's good, it's extraordinary - complex, unpredictable, and capable of flavour profiles that few other coffees can match. It demands attention from the farmer, care from the roaster, and rewards anyone willing to seek out the exceptional lots.

That's why we keep going back to producers like the Mierisch family, asking questions, running experiments, and tasting everything we can. Pacamara isn't just a varietal we sell - it's one we genuinely love.

Further Reading: World Coffee Research Arabica Coffee Varieties | Pacamara